The Rise of AI Actors

AI-generated performers are stepping into the spotlight, with figures like Tilly Norwood sparking debate across Hollywood and beyond. This article explores the rise of AI actors, their benefits, and the backlash from unions and human performers.g post description.

GENERATIVE AI

Robin Lamott

10/4/202513 min read

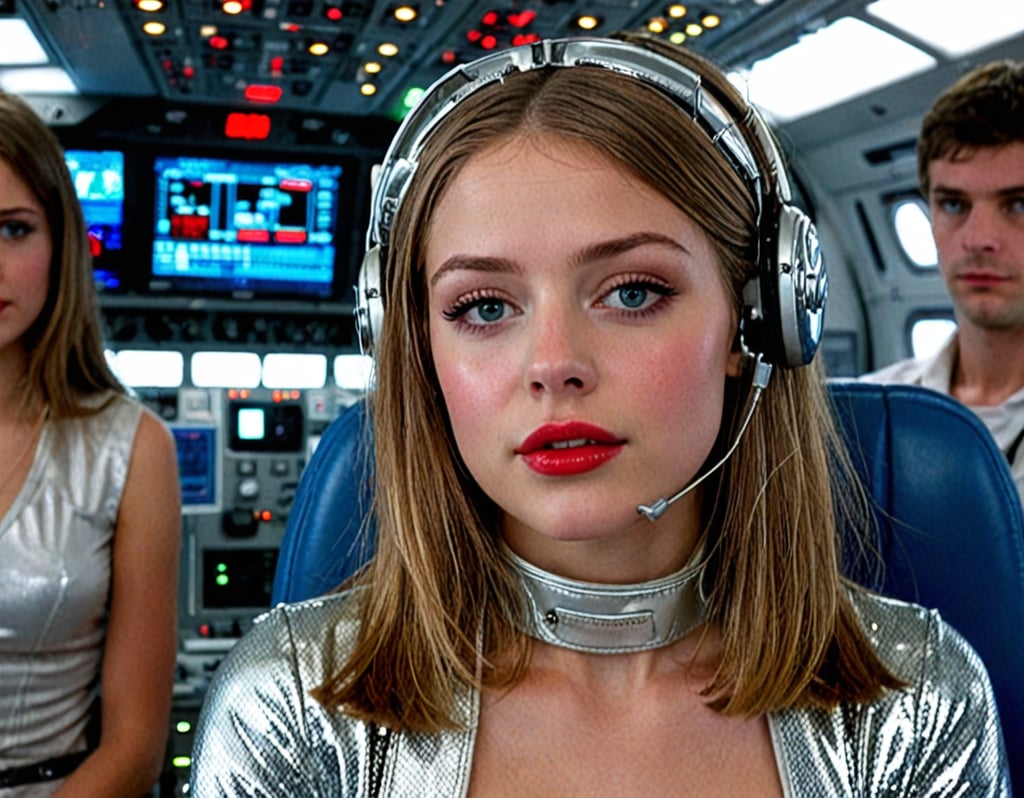

There’s a new kind of performer in town: photoreal, camera-ready faces and voices born in code, marketed like rising stars, and sometimes even seeking representation. This isn’t science fiction anymore — the entertainment world is wrestling with AI-generated “actors” that can be posed, lit, directed, and tweaked without a human body on set. The recent debut of Tilly Norwood, an AI-generated “actor” introduced this year and immediately catapulted into headlines, crystallizes the moment. Newspapers and industry groups called it provocative; unions and many performers called it dangerous. Fans, technologists, and advertisers saw opportunity. The ensuing debate strips down to a few essential questions: what can AI actors do well, what can they never replace, and how should an industry built around people adapt to a technology that can impersonate them?

Below, I unpack the story — using Tilly as a focal example — then widen the lens to other digital performers (from virtual influencers to Vocaloid stars), the practical benefits of AI actors, the legitimate anxieties raised by unions and performers, and a pragmatic roadmap for how the industry could move forward without burning bridges.

What happened with Tilly Norwood — why she matters

Tilly Norwood’s public debut this year pushed virtual performers from social feeds and marketing experiments into a mainstream media spectacle. Created and promoted by a production group as a lifelike, “representable” AI performer, Tilly was framed by her makers as an artistic work and a new kind of creative asset — a digital persona that can appear in photo shoots, short films, branded content, and even audition tapes. Within days of the reveal, major outlets reported that talent agents had been approached about representing her, and that studios and brands were quietly discussing projects. That attention is what made the reveal feel like more than a stunt: Tilly’s creators were actively trying to fold an AI-generated person into the same commercial pipeline that handles human actors.

The reaction from the industry was immediate and intense. Actors’ unions, led by voices within SAG-AFTRA and international counterparts, issued strong critiques: AI creations that look like real people and are being marketed as actors threaten to displace performers, bypass licensing and consent norms, and undermine the human-centered nature of acting. Headlines and opinion pieces asked whether studios would favor never-needy, easily-updated virtual talent over living performers — and whether “representation” for an entity with no legal personhood should ever be entertained. That anger and policy pressure pushed the discussion beyond tech circles and into the halls of guilds, agents’ offices, and festival programmers.

(Those developments — the publicity, the agent interest, the union statements — are exactly why Tilly is useful as a case study: she’s not the origin story of virtual performers, but she’s the first one to deliberately aim for mainstream industry legitimacy as an “actor,” rather than remaining purely a brand or experimental art project.)

A short history: digital performers weren’t invented yesterday

If we step back, the concept of non-human performers has a long and varied history. Japanese virtual singers like Hatsune Miku predate modern neural nets and have headlined stadium concerts, starred in commercials, and become a global franchise — showing that audiences can form deep attachments to synthetic personas when the cultural and commercial framing supports it. Virtual influencers like Lil Miquela and digital models such as Shudu have worked with fashion brands, published sponsored content, and built followings that rival human influencers. And in music, AI or algorithm-driven projects such as the controversial AI rapper FN Meka have sparked debates about representation, cultural sensitivity, and corporate responsibility. These precedents show the cultural appetite for digital personas — but they also illustrate how easily they can provoke ethical and social backlash when creators ignore context, representation, or consent.

There’s also a technical lineage. Filmmakers have long used digital doubles, CGI recreations, and voice synthesis to fill gaps — for example, digitally recreating an actor who has died or was unavailable. Those uses historically relied on heavy VFX pipelines and large budgets. Today’s difference is scale and accessibility: machine learning tools can generate believable faces, expressions, and even speech with far fewer resources, which lowers the barrier for creating photoreal digital actors and puts the power to make them into the hands of studios, startups, and independent creators alike.

Who qualifies as an “AI actor”?

That’s a deceptively important question. The label “AI actor” lumps together very different cases:

Digital influencers and virtual models (Lil Miquela, Shudu) — characters created as marketing and entertainment properties, often with scripted social media personas. They are designed to interact with fans and brands rather than to perform dramatic roles in film or TV.

Virtual idols / Vocaloids (Hatsune Miku) — characters whose “performances” are driven by synthesized vocals and choreography; their artistry is a hybrid of fan creation, composer tools, and corporate licensing. These acts have real commercial value and touring infrastructures.

AI-generated actors intended for dramatic roles (the Tilly Norwood model) — photoreal personas created to occupy the same commercial and professional space as human actors: auditions, representation, and credited roles.

Partially synthetic performances — live-action projects that use human performers augmented by AI for voice, face replacement, or de-aging (examples exist historically in VFX-driven films).

Voice-only AI “actors” — voices synthesized from datasets or cloned from specific actors (closer to voice-over territory but equally disruptive).

Each category raises overlapping but distinct questions — ethical, legal, creative, and economic. The current flashpoint is the third category: companies are now packaging photoreal AI personas not just for branding or music, but to be cast as “actors.” That is what makes recent headlines so consequential.

Why studios, brands, and creators are building AI actors — the concrete benefits

There are practical, business, and creative reasons behind the rush. Some of them are immediate and obvious; others are more nuanced.

Cost and control. Synthesizing a performer removes recurring costs tied to travel, per-day shooting rates, union residuals, insurance, catering, and on-set logistics. A digital performer can be shot in a fraction of the time through render pipelines and compositing, and studios can make changes without having to re-book an actor. For brands pushing high-volume content with tight turnarounds, that efficiency is attractive.

Scalability and availability. A digital performer can exist in multiple places at once: different localized ad versions, different languages, different visual styles — all without scheduling conflicts. That flexibility is appealing for global campaigns, iterative testing, or franchisable IP.

Creative control and infinite edits. Directors and creative teams can “tweak” performances frame-by-frame with different facial expressions, wardrobe, or even subtle changes in emotional tone — enabling a kind of iterative perfectionism that traditional shoots can’t provide without costly reshoots.

New forms of storytelling. Some creators imagine stories that are inherently better told by synthetic beings — interactive narratives, real-time virtual co-stars, or experiences where the performer’s nature is part of the fiction. Virtual idols and AI-driven characters create novel audience engagement models, including live, improvised shows mediated by AI.

Preservation and archival use-cases. There are legitimate, compassionate uses: preserving the voice and likeness of a late performer for an authorized tribute, or recreating historical figures for documentaries when handled with consent and sensitivity.

Lowering barriers to entry. Independent filmmakers and small studios without the budgets for big-name casts can prototype scenes, proof-of-concepts, and visual pitches using synthetic talent — potentially democratizing certain production workflows.

Those benefits explain the business appetite. But appetite doesn’t absolve responsibility; the ethical and legal ripples are real and immediate.

The unions and the knee-jerk reactions — why actors and guilds pushed back

When news broke about AI-generated “actors” being positioned to seek representation and roles, actor unions and high-profile performers reacted forcefully. The response included public statements condemning AI replacements, calls for protective bargaining measures, and renewed demands for clear consent and licensing frameworks. SAG-AFTRA and several international counterparts publicly warned that synthetic performers threaten performers’ livelihoods and that human creativity must remain central to storytelling.

Why was the reaction so fast and angry? A few reasons:

Economic threat: The prospect of employers substituting synthetic performers for background actors or even speaking roles — especially in lower-budget, high-volume content — would immediately shrink job opportunities. For performers who live gig-to-gig, even modest shifts in demand can be devastating.

Consent and likeness issues: Historically, studios have had to negotiate likeness, residuals, and moral-rights protections. AI actors that echo the features of real people — or are trained on datasets containing images of real actors — raise the specter of unconsented imitation. The union rhetoric highlights the need for explicit licensing and compensation whenever an actor’s voice or appearance is used.

Artistic integrity: Acting is not just a set of facial muscles in motion; it’s the accumulation of lived experience, craft, improvisation, and chemistry with other actors. Unions argued that replacing artists with synthetic composites devalues this craft.

Precedent and leverage: Labor organizations mobilize quickly to set norms. Because we’ve already seen AI-related fights over writers’ and actors’ rights in recent industry strikes, unions are wary of being slow to respond again. Proactive statements and bargaining positions help define acceptable uses before they become standard practice.

It’s fair to describe some of the initial union responses as “knee-jerk” in tone — a strongly defensive reflex to a perceived existential threat. But they’re also strategic: public pressure, legal claims, and collective bargaining are among the few levers performers have to shape how technology is used in their industry. What looks like reflex can also be a rational labor-protection strategy.

Are the unions overreacting? Parsing the hyperbole

There’s a spectrum between dystopia and denial.

Not everything AI does is replacement-level. Many AI “actors” are not autonomous creators; they are tools or assets. A photoreal digital character still requires a creative team — writers, animators, voice designers, directors — and often a human in the loop for emotional nuance. For large-budget films, star power, box-office draw, and the unique chemistry of a human cast still matter immensely.

Technical limits remain. Despite impressive generative models, there are subtleties of micro-expression, improvisation, and authentic emotional unpredictability where human performers excel. Viewers often detect “the uncanny” even when a digital face is photoreal, and that can harm audience engagement in dramatic storytelling.

Business models will evolve. Rather than wholesale replacement, early adopters may use AI actors for certain classes of work (ads, background characters, crowd scenes, localized content), while leaving marquee roles to humans. The most likely immediate effect is displacement in low-cost, high-volume corners, not an instantaneous mass obsolescence of professional actors.

So while the unions’ anxieties are grounded, scenes painted as “the end of acting” are hyperbolic at present. That said, hyperbole isn’t harmless: it can harden positions and make compromise harder. The better route is policy and contracts that protect people while enabling creative experimentation.

Real harms and real ethical red lines

Not all pushback is overblown. There are concrete, demonstrable harms to guard against:

Unauthorized likeness use and deepfakes. AI systems trained on image datasets containing real people can inadvertently reproduce or approximate living actors’ faces. If companies use those outputs commercially without consent, they risk legal and reputational consequences. (This worry is at the heart of many union statements.)

Bias and cultural harm. Historical cases like the FN Meka controversy show how synthetic personas can perpetuate stereotypes or commit cultural appropriation if creators don’t thoughtfully design datasets and teams. That controversy led to a major label severing ties and highlighted the social risk of letting AI companies design cultural expression without diverse oversight.

Job displacement for supporting artists. Beyond principal actors, whole ecosystems — makeup artists, wardrobe, grips, background actors — could face diminished demand if synthetic production pipelines scale. That’s a labor concern unions watch closely.

Erosion of standards for consent in sexualized or vulnerable depictions. Synthetic actors can be made to appear young or to be placed in sensitive contexts without the constraints that govern human performers, raising exploitation concerns. Advocacy groups and specialized organizations have already raised alarms about how this could be misused.

Monopolies on attention. If a few corporations own the most compelling virtual talents, they could dominate certain advertising and social media spaces in ways that squeeze out diverse voices.

These aren’t theoretical; they’re already playing out in public controversies and hence demand preemptive policy thinking.

Productive paths: how the industry can regulate and integrate AI actors responsibly

There’s no single silver bullet, but several practical measures can reduce harm while allowing innovation:

Clear consent and attribution laws. Make it illegal (or at least legally risky) to commercialize a synthetic persona that meaningfully resembles a living person without explicit, documented consent and compensation. Contracts should require data provenance disclosure — where training images came from — for any commercially used synthetic face.

Strong union bargaining language. Unions should negotiate clauses that define permissible AI usage, require transparency when AI tools are used on set or during post-production, and secure residual-style compensation where synthetic reproductions derive value from performers’ likenesses or brands.

Dataset transparency and auditing. Companies creating AI actors should be required (or incentivized) to publish audits describing datasets, steps taken to mitigate bias, and processes for removing problematic or copyrighted material. Independent audits could certify safer datasets.

Age and consent safeguards. Platforms and creators should have clear rules forbidding the creation of sexualized or underage-appearing synthetic personas, and robust moderation to prevent misuse.

Licensing frameworks for digital clones. If an actor wants to license a digital “clone” for commercial use, standardized licensing templates could simplify compensation and reuse terms, creating a market where human performers retain agency and benefit economically.

Ethical labelling and audience disclosure. Require clear disclosures when a performer is synthetic or when a human performance has been substantially altered by AI, much like content warnings. Audiences deserve to know when what they’re watching is produced by humans, machines, or both.

Support for displaced workers. If certain production roles shrink, studios and unions should collaborate on re-skilling programs, transitional pay, and grants that help technicians move into new digital roles (e.g., virtual production, motion-capture direction, AI supervision).

These measures align labor protection with technological realism: AI will be part of production workflows, so governance frameworks should ensure human artists are respected, compensated, and protected.

Creative possibilities we shouldn’t lose sight of

Beyond the controversies, AI actors unlock creative doors that are already proving useful:

Interactive storytelling and live experiences. Imagine a living virtual co-star who can respond to audience input in real time for immersive theater, education, or therapy contexts.

Representation through design. Thoughtfully created virtual performers can increase representation in media — when designed with diverse teams and ethical practices, they can embody identities and experiences that are underrepresented in mainstream casting.

Safety in risky shoots. Stunts, dangerous scenes, or hazardous environments might be simulated with synthetic performers to reduce risk to human life during production.

Archival and educational uses. Authenticated, licensed digital doubles could play roles in preserving cultural heritage, allowing historical recreations that are educational and clearly labeled as such.

Cost-effective localization. Brands and franchises can localize performances across languages and regions by adjusting a digital performer’s speech and mannerisms, making global storytelling more accessible.

If governed well, these opportunities can enrich the entertainment ecosystem, create new jobs (AI directors, ethicists, virtual performance coaches), and broaden the range of stories we can tell.

Practical examples to illustrate the spectrum

Hatsune Miku (Vocaloid): A decades-old example of a non-human performer who became a global cultural icon. Miku demonstrates how audiences can embrace a synthetic star when the creative community, rights holders, and fans shape her use and evolution. Her success highlights the potential for virtual performers to become permanent, beloved fixtures rather than mere curiosities.

Lil Miquela and Shudu (virtual influencers/modeling): These virtual personas have been used for brand campaigns and editorial work, proving that virtual faces can hold commercial value in advertising and social media. Their careers also show the reputational risks when creators obscure the commercial or constructed nature of these characters — transparency matters.

FN Meka (AI rapper controversy): A cautionary tale: a highly publicized AI music project was dropped by a major label after accusations of racist stereotyping. The backlash illustrated how cultural sensitivity and diverse creative oversight are essential when deploying synthetic performers.

Tilly Norwood (AI actor seeking representation): The recent Tilly saga crystallized the labor and legal questions by pushing a photoreal digital persona into the agent/studio conversation and prompting union statements. She’s a real-world stress test of policies that haven’t yet been fully formed.

These examples show both promise and peril — the difference often lies in governance, transparency, and inclusion.

What actors and creatives can actually do right now

If you’re a performer, an agent, a creative, or a studio executive wondering how to respond, here are practical steps to protect artistic value and livelihoods while adapting:

Document and vaccinate your likeness. If you don’t want your face, body, or voice used in synthetic creations without payment, be proactive: negotiate contract language that specifies explicit rights for digital reproductions, requires consent for AI usage, and secures compensation for derivative uses.

Educate your team. Agents and managers should learn what AI can and cannot do today so they can bargain from a position of knowledge. Unions and studios should share educational resources and workshops.

Drive transparency clauses. Seek clauses requiring production companies to disclose AI use in advertising, post-production, and casting decisions.

Push for audit requirements. Demand that projects using synthetic talent disclose the sources of their training data and offer independent audits when likeness claims are raised.

Experiment on your terms. For artists interested in the technology, licensing your own digital clone under controlled terms can create new revenue without ceding control.

Build alliances beyond the industry. Collaborate with technologists, ethicists, and regulators to create frameworks that are both protective and flexible.

The actors who will thrive are those who treat AI as both a risk to manage and a tool to harness on their own terms.

Legal and policy trends to watch

Lawmakers and courts will play a major role in defining the future landscape. Key areas to monitor:

Right of publicity laws — statutes that protect a person’s commercial use of their image and likeness differ widely by jurisdiction; some regions offer stronger protections than others.

Copyright and dataset regulation — litigation over whether training on copyrighted images is infringement is moving through courts and could set precedents about how AI models are trained and what outputs are permissible.

Labor agreements — union contracts negotiated during collective bargaining can set industry-wide standards for AI usage, residuals, and disclosure. Given recent strikes and negotiations, this is a live area.

Platform liability and labeling rules — governments and platforms may mandate labeling of synthetic media, especially when deployed in advertising or political content.

Keeping an eye on these fronts will help artists and companies anticipate regulatory change and adapt early.

A realistic closing: coexistence, not annihilation

The fear that AI will instantly replace actors is understandable but, in most realistic scenarios, overstated. The more probable near-term outcome is nuanced coexistence: synthetic performers will be used where they make economic or creative sense (ads, virtual influencers, specific VFX work), while human performers continue to anchor mainstream film, TV, and theater — especially where authenticity, charisma, and improvisation matter.

That doesn’t mean the status quo is safe. Left unchecked, AI-driven efficiencies could hollow out middle-class gigs and informal economies that support creative life. That is why the current union push — and the high-profile debates sparked by projects like Tilly Norwood — matter. The industry is being forced into conversations about consent, pay, and artistic value that needed to happen anyway.

If we want a future where both human and synthetic performers enrich culture, the path requires deliberate policy, transparent business practices, and an insistence that artists — not just code — remain central to storytelling. We should be pragmatic about the utility of AI actors (they can innovate, expand access, and enable new forms of art) while clear-eyed about the risks (unauthorized likeness use, displacement, and cultural harm). Where possible, design frameworks that let artists license and benefit from the technology, not be displaced by it.

Final thoughts: what to hope for

Hope for responsibility: Corporations and creators will adopt best practices for consent, transparency, and compensation rather than chasing short-term gains at human expense.

Hope for creativity: New genres and interactive experiences will blossom because creators can prototype and experiment cheaply with convincing virtual collaborators.

Hope for solidarity: Unions, technologists, and policymakers will find common ground to shape fair, enforceable rules that protect workers while permitting innovation.

Tilly Norwood and others like her are not the end of acting — they’re a mirror held up to the industry. They force a crucial reckoning: do we want to outsource parts of our creative lives to tools that prioritize efficiency, or can we find ways to design those tools so that the humans who make art are respected, celebrated, and fairly rewarded? The answer will shape the next era of storytelling.

© 2025. All rights reserved.